Right now, the world can feel like a joyless place for LGBTQ+ people, but queer joy is not only possible, it' s an act of resistance.

President Donald Trump’s systematic attack on the rights of LGBTQ+ people has made the world a scary place to live in. He has ended federal funding for gender-affirming care, denied LGBTQ+ people access to the HIV prevention medication PrEP, reinstated a ban on trans people serving in the military, and signed the anti-trans “No Men in Women’s Sports” executive order. It would be easy to fall into despair and hopelessness, but this is not the first time our community has felt this kind of existential dread and fear for our future. The queer community has fought back and won before, and we can and will do it again.

To empower ourselves in the present, it's essential to understand our past. In 1981, doctors started identifying the disease that would later become known as HIV/AIDS in gay men in Los Angeles, San Francisco, and New York City. By 1986, more than 11,000 people had died from AIDS-related complications in the United States, and yet rampant homophobia led to a lack of social services, inaction by the government — former President Ronald Reagan didn’t even say the word AIDS until 1985 — and little scientific advancement.

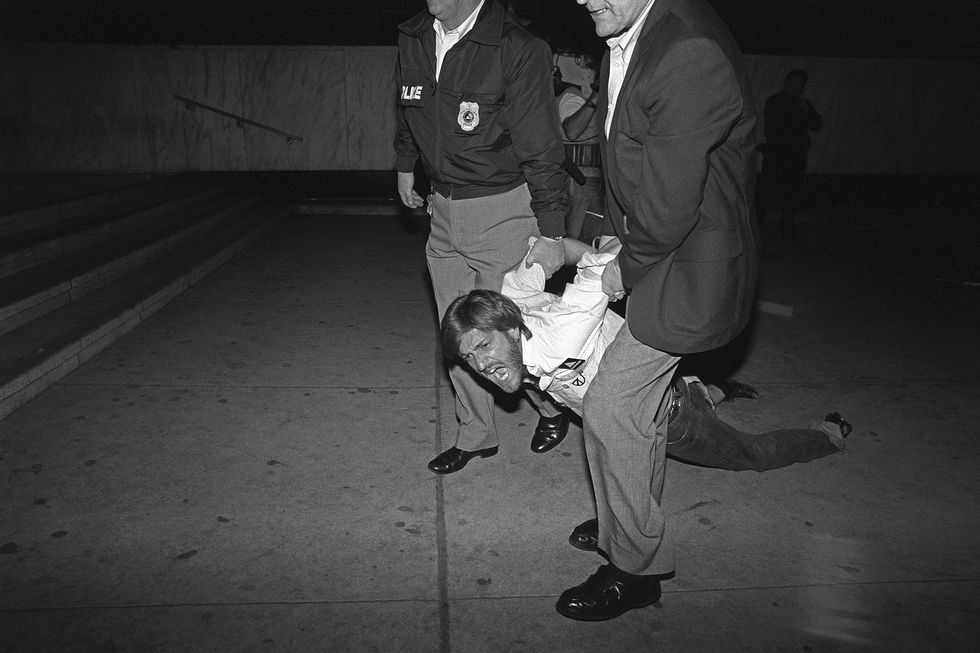

During the height of the AIDS crisis of the 1980s and ‘90s, people took to the streets en masse, marching and participating in nonviolent direct action and acts of civil disobedience to demand structural change and fight against the inexcusable neglect of the deaths of thousands within the queer community. And while the fight to create real change is long, arduous, and often exhausting, we’ve won before by embracing and fighting for queer joy as much as queer rights.

As Dan Savage, Savage Love writer, LGBTQ+ activist, and co-creator of the It Gets Better Project, posted on Instagram in the wake of the 2024 election, “During the darkest days of the AIDS crisis, we buried our friends in the morning, we protested in the afternoon, and we danced all night. The dance kept us in the fight because it was the dance we were fighting for. It didn’t look like we were going to win then and we did. It doesn’t feel like we’re going to win now but we could. Keep fighting, keep dancing."

The movement to fight back against a system that was failing queer people across the country was led by the AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power (ACT UP), a grassroots activist coalition born out of the collective anger at the social and governmental neglect of people with AIDS and the 1986 U.S. Supreme Court case that upheld the constitutionality of anti-sodomy laws. ACT UP organized marches, stunningly brave acts of civil disobedience, and worked to destigmatize queer sex, but also knew that building community, celebrating their sexuality, and finding moments of happiness were also crucial.

Growing up in the ’80s and ‘90s in the San Francisco Bay Area with an out-lesbian mother meant that the AIDS crisis was ever present in my childhood.

I watched my mother protest in the streets, even as she took care of her gay friends who were dying and had been abandoned by their families. I went to countless funerals. The first memorial service I ever attended was for my godmother’s brother, who died of AIDS-related complications. I was five or six years old, and I vividly remember helping to plant a rose bush in her garden, where we spread his ashes while the adults around me sobbed.

As an activist, my mother was part of an affinity group — a small group of people who support each other during demonstrations and protests — that worked closely with other groups, including an affinity group comprised of gay men. Shockingly, all twelve of them had passed away by the time the early ‘90s rolled around.

I watched as she mourned these men and saw her devastation at losing her best friend to the disease. I also bore witness to her planning protests, including the time she and other activists shut down the Golden Gate Bridge in an attempt to raise awareness of the crisis and demand the government step in to alleviate the suffering.

But I also remember that even though death and tragedy became an ever-present fact of life, my mother and her queer friends found ways to be joyful, and this joy allowed them to keep fighting back even amid all the grief.

“There was joy and gathering together in communal spaces that was not just important but necessary for survival,” ACT UP activist Sean Strub told PRIDE. “People were still making art, falling in love, breaking up, pursuing careers, raising families, etc., despite also experiencing profound loss and having to take care of each other as we were dying.” Strub co-chaired ACT UP’s fundraising committee, was the first openly HIV+ person to run for Congress, founded both POZ Magazine — which chronicles the lives of people with HIV/AIDS — and the Sero Project — which focuses on ending the criminal prosecution of people with HIV — and authored the book Body Counts: A Memoir of Politics, Sex, AIDS, and Survival.

Today, even as our government is becoming more repressive and police forces across the country are becoming more violent toward even nonviolent protesters, it’s important to remember that having fun, celebrating your sexuality, and finding moments of queer joy isn’t just a way to keep your spirits up, but is also an act of rebellion all on its own.

“In every resistance movement, even under the most awful oppression, even in refugee camps and prisons, there are aspects of joy,” Strub said. “I'll bet someone has studied this in Vichy France and elsewhere. At POZ we once sponsored a POZ comedy night and it was a huge success. Some were appalled: ‘What's funny about AIDS?’ But keeping our sense of humor, finding love, companionship, creating art and music and celebration are a necessary fuel to drive the resistance, to ultimately overcome.”

Trump’s attack on the rights of the LGBTQ+ community has been so disheartening to witness that it would be easy to lose faith that anything can be done. But as you rally to fight back, it’s important to remember that real change often takes years, not months, so you have to find ways to keep your hope alive — and keep fighting.

“If you’re not in the streets today; If you’re not dedicating a significant portion of your energy, time, and resources to combating what’s going on; how much worse would it have to get for you to do so?" Strub asked. "We are in wartime and last November we lost, badly, the biggest battle to date. Millions of lives are at stake, the community we've created and the rights we've fought for and gained are at tremendous risk.”

Activism is incredibly rewarding but can also be exhausting, which is why ACT UP activist Anne-christine d’Adesky, who also co-founded the direct action group the Lesbian Avengers, is about to host a cabaret at her house for her birthday “because we need to dance together.”

“Fun has to be part of the formula for me because it will continue to draw people, and it continues to bond us,” said d’Adesky, who helped to organize the very first Dyke March and has had a storied career as an award-winning journalist for publications like the Village Voice, The Advocate, Out, launched HIV Plus Magazine, and has dedicated much of her recent activism to combating Project 2025.

She called the current political climate “both a horrible time and an incredible time in the sense that repression forces people to survive,” remarking that ACT UP was started because people were fighting for their survival and what she called “Trump 2.0” is creating a similar situation today that is giving people a common cause to fight for.

d’Adesky said that turning up for national protests is important because “we need the numbers out on the street” to “make public opposition to this regime visible,” but you can make an even bigger impact at a local level through mutual aid or doing things like speaking to your representatives in person.

“The more that happens, the more effective our resistance, and the more they will feel that they’re part of a movement,” d’Adesky said. “That they’re not isolated at home. That they’re not sitting there at home not knowing what to do or how to plug in.”

Jordan Peimer, an ACT UP Los Angeles activist and the co-creator of ACT UP LA’s oral history project, said that on top of doing the important work of organizing and protesting, building community, celebrating together, and even flirting with other protestors and having sex was part of what kept members of the group going.

“There were far too many funerals, and there were far too many protests. Sometimes all you could do was dance,” he said.

Peimer — who got more involved in the movement in 1988 after participating in an overnight vigil at LA County General Hospital where he saw firsthand how terribly AIDS patients were being treated — said activists of the past benefited from having to meet up face-to-face to organize, protest, and party together, and cautioned that “sitting behind a computer screen is demoralizing.”

Although you may be feeling grief, existential terror, and frustration, today’s queer activists need to use queer joy as a weapon of resistance so we have the emotional energy to fight another day. Despite setbacks and even major losses, the protest movements of the past have taught us that real change is possible.

“I get it, it is way easier to click on a computer screen but it doesn't feed your queer soul,” he explained. “The Trans community just scored a partial victory in LA against the Children's Hospital by coming together to protest their lack of gender-affirming care when Children's Hospital LA reversed their recently enacted restrictions on gender-affirming care. That would not have happened if people stayed at home. It wouldn't have happened for me as seriously if I hadn't spent the night at the Los Angeles County General Hospital Vigil. Show up for your community: you'll be less tired and defeated, and who knows, you might get laid!”